As more employers consider launching formal employee wellness programs, academic research supporting and questioning the efficacy of these initiatives continue to grow. Likewise, skepticism regarding the methodologies used in the research increases. Most notably, an article in The Upshot analyzed the power of randomized controlled trials relative to observational studies when conducting explanatory research. The article used employee wellness studies as the example, showing that observational studies may show positive impacts from employee wellness programs in relation to healthcare expenses while a randomized controlled trial may tell a different story.

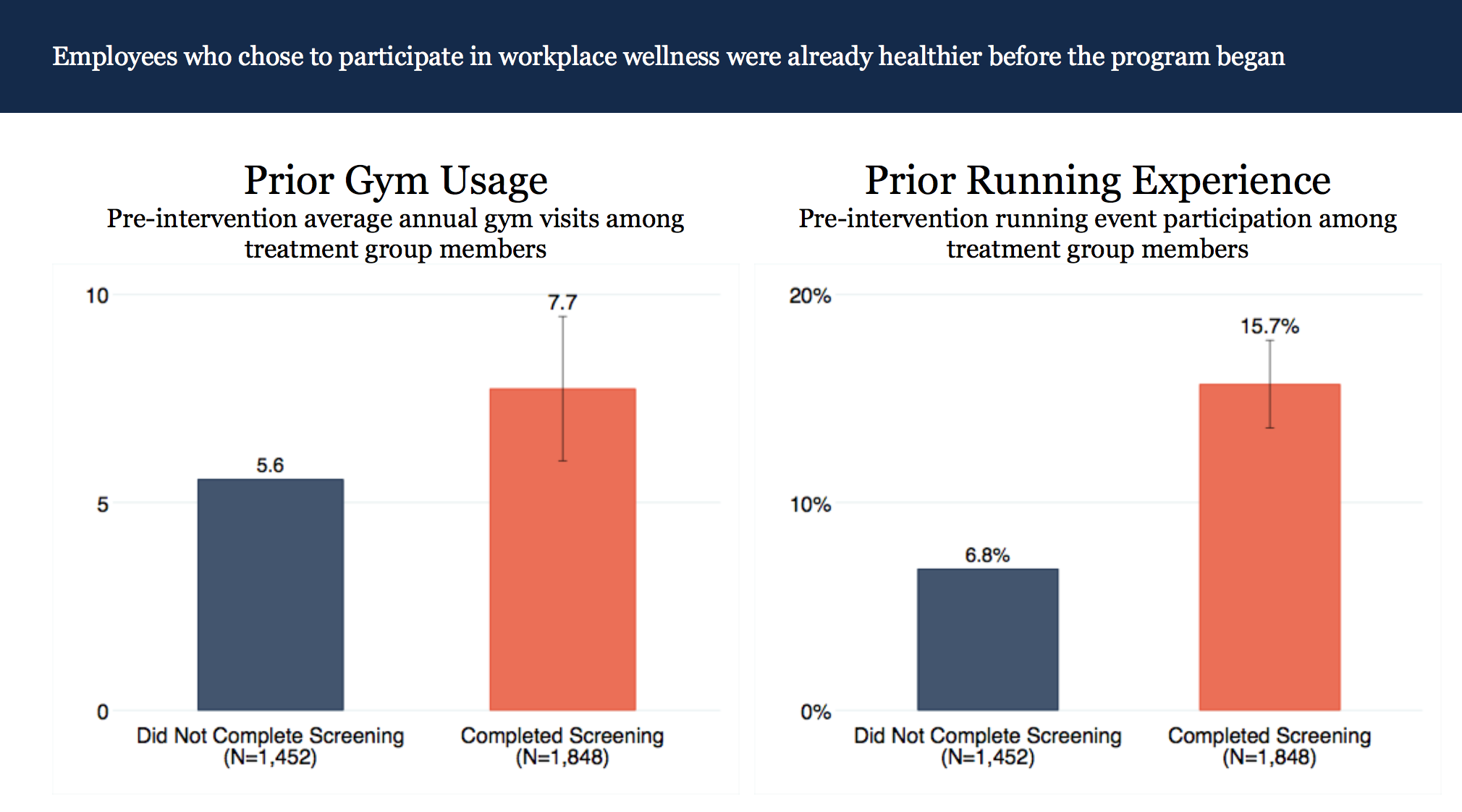

The article reviewed the findings of a randomized controlled trial study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research that questioned the positive impact employee wellness programs have on program participants. Wellable has addressed this study comprehensively through a blog post summarizing the results, a podcast with the lead researchers, and a Whiteboard Wednesday video focusing on one specific element of the research. In short, the study found that people who participate in wellness programs already lead healthier lives, and thus, an observational study would “observe” that wellness program participants have lower medical expenses. When using a randomized controlled trial study, the researchers determined that the superior health of program participants is likely a result of selection bias (healthier employees choosing to participate) rather than the impact of the program itself.

When analyzed appropriately, the findings of the study grants business leaders the capability to make more informed decisions regarding implementation of wellness programs and initiatives. However, all relevant information needs to be weighed. Because the main objective of The Upshot article was to contrast two methods of study, there are two specific aspects, understandably left out from the article, that are valuable to business leaders.

First, not all wellness programs are equal. The wellness program analyzed in the study included a biometric screening and an online health risk assessments (HRA) as main components. Employers do not need more research on why services like biometric screenings and HRAs are ineffective, as this has been proven time and time again. These services present little benefit for participants, and employees in poorer health may even feel discouraged or alienated by them. Since the study researched an employee wellness program that included services known to be ineffective, it should not come as a surprise that the results question the efficacy of wellness programs in general. Both of these reasons may contribute to the selection bias.

Second, the study inherently assumed that the sole goal of employee wellness programs is to lower medical expenses. This is a very “return-on-investment” perspective that employers are increasingly abandoning for a “value-on-investment” perspective. As noted by the researchers in the study, employee wellness programs could serve as “screening mechanisms” for differential recruitment and retention of lower cost employees, which could result in financial returns despite the absence of direct savings from lower medical expenses. When expanding the value to include productivity gains and higher engagement, the verdict of employee wellness programs will likely shift.

The main takeaway is that The Upshot article, while correct in some regard, is considerably incomplete. It is correct in that randomized controlled trials are much more effective tools in explanatory research and that observational studies, especially in employee wellness research, often elicit flawed results and explanations that fail to be confirmed in other, more rigorous studies. The article is lacking, however, in that a casual reader may finish it thinking that all employee wellness programs are bad, which is neither the case nor the point the author was trying to make. In the end, effective wellness programs are largely determined by the type of initiatives that constitute the program and the goals of the employer. If the program includes ineffective solutions and/or has the expectation of lowering medical expenses, it is likely to fail, both in the eyes of the employer and the employees.