Cognitive impairment, inciting the onset of various dementias, persists to be a major health concern, plaguing over 16 million people in the United States alone. While lifestyle changes, including increased physical activity, continue to be the most viable option in combating cognitive decline, CDC National Health Statistics Report shows that less than a mere quarter of American adults are meeting daily exercise guidelines.

There is no absence of evidence proving that sedentary behavior precipitates a variety of health concerns, but recent studies have illustrated that prolonged sitting could actually be a contributing cause of neurodegenerative diseases as well.

Prolonged Sitting And The Brain

Healthy cognitive function is contingent on consistent blood flow, which delivers vital oxygen and nutrients to the cells of the brain. Although this process is regulated automatically, small fluctuations, induced by different behaviors, do occur. While these minor inconsistencies may seem insignificant in the short-term, they accumulate over time and contribute to long-term cognitive impairment.

A recent study from Liverpool John Moores University in England explores the effects of prolonged sitting on peripheral blood flow and function. Researchers recruited 15 healthy adults for observation, all of whom had worked in an office setting and were previously accustomed to sitting for multiple hours each day.

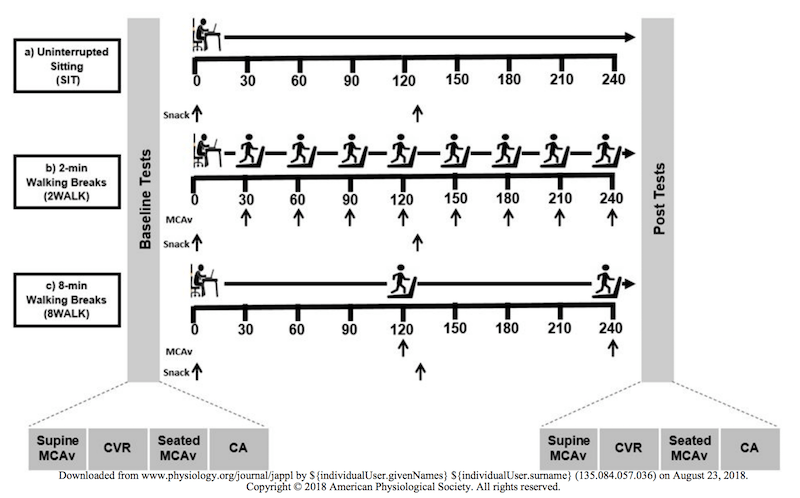

Individuals were asked to attend three four-hour office simulations, each held on a different day in no particular order. The circulatory function of their cerebral arteries and the carbon dioxide output from their breath were evaluated, respectively, via ultrasound headbands and masks. During one session, individuals remained seated at a desk for the entire duration of the simulation. During another session, they were instructed to sit for 30 minutes at a time, getting up to walk at a leisure pace on a nearby treadmill for two minutes in between each interval. The last session required that the individuals sit for two hours intervals, getting up once in between to walk on the treadmill for eight minutes at the same leisure pace.

Although the carbon dioxide levels surprisingly remained unchanged before and after each session, the changes in blood flow were consistent with the researchers’ predictions. As anticipated, there was an evident decline in blood flow when individuals remained sedentary for the entire four-hour session. The same effect was observed when individuals sat for two-hour intervals; though their blood flow increased during the eight minutes of activity, it decreased once more, even lower than the initial reading, after their second sedentary period.

However, when the session was broken up into 30-minute intervals by frequent periods of brief physical activity, the researchers observed an increase in blood flow amongst the participants.

It is important to note that this study, small and conducted over a short period of time, did not deliberate the individuals’ ability to think or complete tasks. The methods of study for each simulation focused exclusively on observing blood flow and carbon dioxide output.

What Does It Mean?

The study, despite neglecting the explicit effects sedentary conditions may have on cognitive ability, does support that immobile behavior decreases blood flow to the brain. Moreover, it is known that restricted blood flow to the brain results in neurodegenerative problems, and as such, it is reasonable to conclude that behaviors that prohibit sufficient blood flow contribute to the onset of cognitive decline.

This is an important matter for employers to consider when overseeing office work. Encouraging physical activity through various wellness initiatives can help protect employees from the risk of cognitive impairment. Given that the vast majority of working adults fail to achieve physical activity recommendations on their own, workplace intervention could be the only viable option for ensuring that employees retain optimal brain health.