In the newly released movie, The Farewell, everyone in the family knows that the matriarch, Nai Nai, only has three months to live—except Nai Nai. The family decides not to tell Nai Nai so she won’t be worried. To see her one last time before she passes, family from the U.S. and Japan go home to China to visit Nai Nai under the guise of attending a wedding.

In the newly released movie, The Farewell, everyone in the family knows that the matriarch, Nai Nai, only has three months to live—except Nai Nai. The family decides not to tell Nai Nai so she won’t be worried. To see her one last time before she passes, family from the U.S. and Japan go home to China to visit Nai Nai under the guise of attending a wedding.

Throughout the movie, some family members felt angst about whether Nai Nai should be told of her fate so she has time to say her own goodbyes. At the end of the movie, which is based on a true story, there is a video of Nai Nai, six years later after the diagnosis, still alive and energetic. She was spared of the unnecessary fear and heartache that would come from hearing a fatal prognosis—even one that turned out to be inaccurate.

The New York Times printed a similar story recently of a man who was told he had a potentially life-threatening liver condition. He had no symptoms; the liver condition was only discovered during routine test to qualify for life insurance. For weeks he lived in limbo, undergoing expensive tests that only served to eliminate possibilities, such as hepatitis, celiac disease, and cancer. Eventually, the diagnosis was drug-induced hepatitis. Through some virus or exposure, his liver became mildly inflamed. After taking an antibiotic for strep-throat, the liver injury increased. The treatment was to watch and wait for the liver to recover.

Should Employers Provide Employees With Routine Tests?

Wellness programs that include biometric testing for all may be doing employees a disservice. The purpose of the examination is to provide employees with insight on their health, allowing them to address any illnesses early on, but when routine testing is done, without symptoms, on a large population, the risk of getting false results is more significant than most realize. Tests are not 100% accurate, which means that some people will be given a diagnosis who are not sick, and others will be told incorrectly that they are healthy.

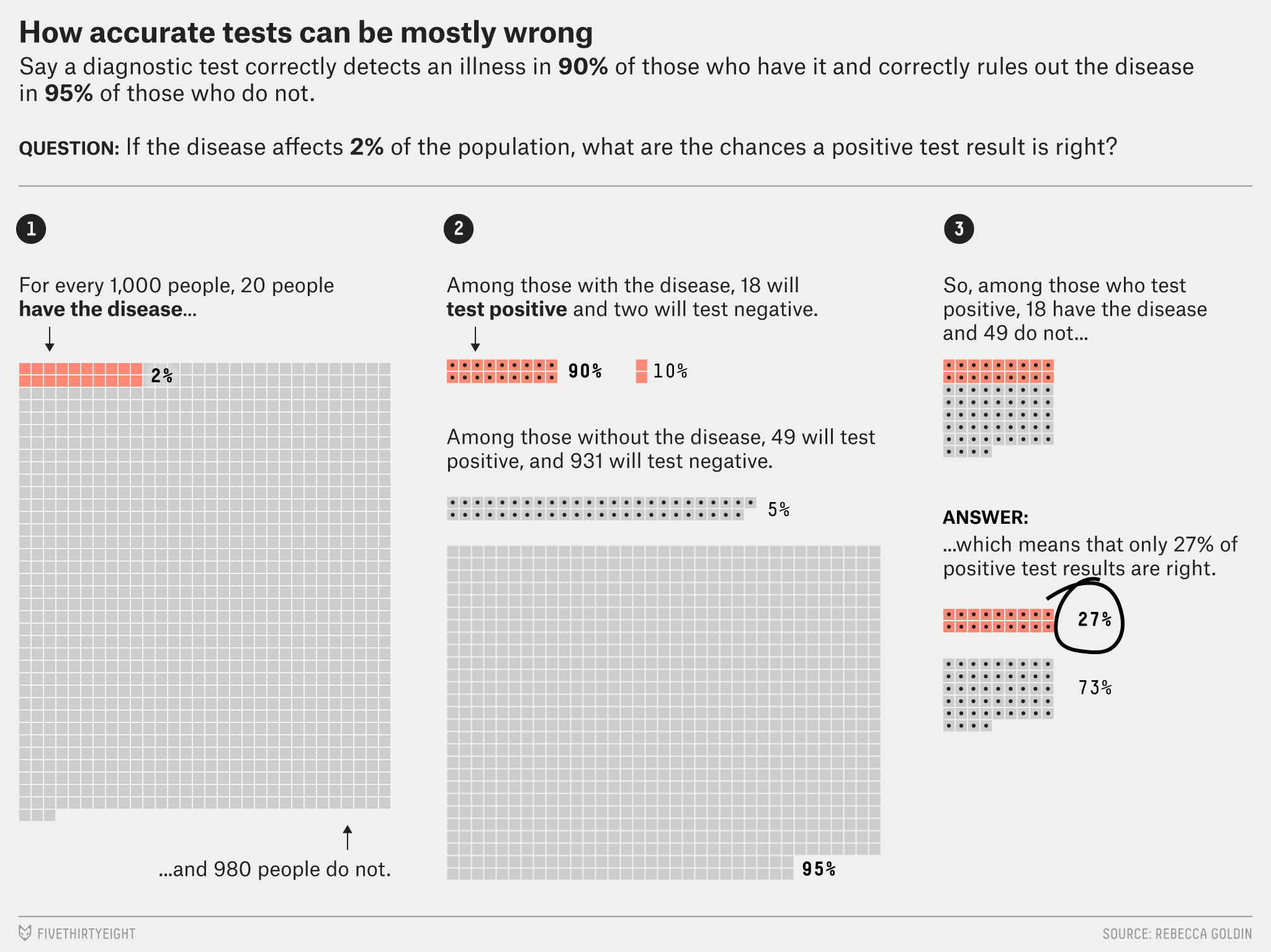

Wellable reviewed the math behind screenings in a hypothetical scenario to demonstrate the risks of false positives and false negatives. The results clearly show that looking for disease through blood tests and other screenings is dangerous because the number of abnormalities outweighs the correct early detection of a disease. Even if a diagnostic test can detect an illness with 90% accuracy and rule out the same illness with 95% accuracy, the number of positive test results, assuming 2% of the population has the disease, is only 27%. Nearly three-fourths of the positive tests would be inaccurate! This is why the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend asymptomatic adults below a certain age get annual physicals and routine blood tests if they are asymptomatic.

If an employee has concerning symptoms of an illness, they should certainly consult with a medical professional, but companies should use caution when considering widespread biometric testing for employees. Instead, ask if the benefits gained from the testing outweigh the risks of an inaccurate diagnosis or the time, financial, and emotional cost involved in correcting the wrong result.

If an employee has concerning symptoms of an illness, they should certainly consult with a medical professional, but companies should use caution when considering widespread biometric testing for employees. Instead, ask if the benefits gained from the testing outweigh the risks of an inaccurate diagnosis or the time, financial, and emotional cost involved in correcting the wrong result.

Had the lawyer not needed a test for his insurance, he would not have spent weeks being poked and prodded and planning out his end of days. Perhaps he would have been like the matriarch, Nai Nai, who was spared being worried unnecessarily.